“Don’t try to be efficient with your grief. Just like healing, moving through grief can be a messy process. An important thing to understand is that you can grieve for years while still living a full and enjoyable life. Letting go is not a quick process, feeling sadness is totally normal, the heaviness of loss can sit in your heart for a long time. The sadness may come up over and over again, sometimes triggered by something small, let it arise and pass away. Let yourself experience grief in an organic manner. Losing someone essential to your life is not an easy thing to overcome.”

Yung Pueblo

“Don’t try to be efficient with your grief. Just like healing, moving through grief can be a messy process. An important thing to understand is that you can grieve for years while still living a full and enjoyable life. Letting go is not a quick process, feeling sadness is totally normal, the heaviness of loss can sit in your heart for a long time. The sadness may come up over and over again, sometimes triggered by something small, let it arise and pass away. Let yourself experience grief in an organic manner.”

Yung Pueblo

“As long as there is love, there will be grief. The grief of time passing, of life moving on half-finished, of empty spaces that were once bursting with the laughter and energy of people we loved. As long as there is love there will be grief because grief is love’s natural continuation. It shows up in the aisles of stores we once frequented, in the half-finished bottle of wine we pour out, in the whiff of cologne we get two years after they’ve been gone. Grief is a giant neon sign, protruding through everything, pointing everywhere, broadcasting loudly, ‘Love was here.’ In the finer print, quietly, ‘Love still is.'”

Heidi Priebe

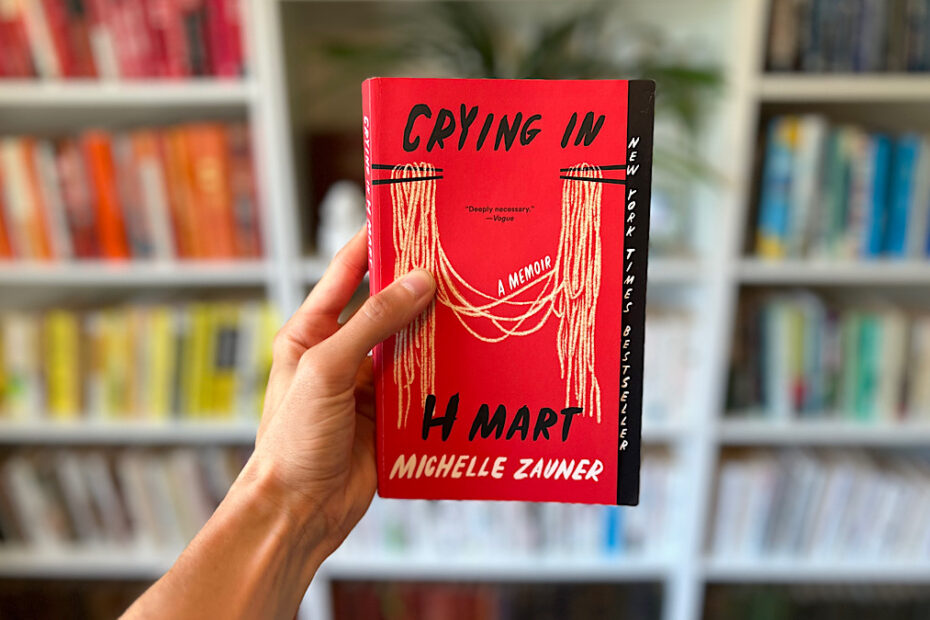

20 Heavy Michelle Zauner Quotes from Crying In H Mart on Cancer and Grief

Excerpt: An honest and raw collection of Michelle Zauner quotes from Crying in H Mart on grief and what it was like losing her mom and aunt to cancer.

Read More »20 Heavy Michelle Zauner Quotes from Crying In H Mart on Cancer and Grief

“The deeper that sorrow carves into your being, the more joy you can contain.”

Kahlil Gibran, The Prophet (Page 27)

“It wasn’t about the money. I wanted to stay as busy as possible. I wanted to work my body as hard as it could go so there was no time to feel sorry for myself, to bind myself to a routine that would keep me grounded in the last remaining months before Peter and I left Eugene for good. Maybe I was punishing myself for my failures as a caretaker, or maybe I was just afraid of what would happen if I slowed down.”

Michelle Zauner, Crying in H Mart (Page 193)

“Most nights, after an early dinner we’d return to our hotel rooms and I’d crumple onto the bed and sleep for fourteen to fifteen hours. Grief, like depression, made it hard to accomplish even the simplest of tasks. The country felt wasted on us. We were numb to all spectacle and feeling, quietly miserable and completely clueless as to how to help each other. All I wanted to do was go home. I longed to hide in my bedroom and dissociate with the comforts of my PlayStation and its soothing farming simulation games, not wake up at six a.m. to take a van tour of another pagoda and marketplace while my father bartered for half an hour over the equivalent of a couple of USD.”

Michelle Zauner, Crying in H Mart (Page 172)

“We figured that maybe if we were busy taking in a place neither of us had ever been, we could manage to forget, just for a moment, how much our lives had fallen apart.”

Michelle Zauner, Crying in H Mart (Page 171)

“It was comforting to hold her work in my hands, to envision my mother prior to pain and suffering, relaxing with a paintbrush in my hand, surrounded by close friends. I wondered if making art had been therapeutic for her, helped her navigate the existential dread that came with Eunmi’s death. I wondered if the late bloom of her creative interests had shed light on my own artistic impulses. If my own creativity had come from her in the first place. If in another life, if circumstances had been different, she might have been an artist, too.”

Michelle Zauner, Crying in H Mart (Page 168)

“When one person collapses [from grief], the other instinctively shoulders their weight.”

Michelle Zauner, Crying in H Mart (Page 153)

“We fell asleep in my childhood bed. We still hadn’t had sex since we got married and as I drifted off, I wondered how I ever could. I couldn’t fathom joy or pleasure or losing myself in a moment ever again. Maybe because it felt wrong, like a betrayal. If I really loved her, I had no right to feel those things again.”

Michelle Zauner, Crying in H Mart (Page 153)

“I knew it was risky to add even more pressure to already tumultuous circumstances, and yet it felt like the perfect way to shed light on the darkest of situations. Instead of mulling over blood thinners and Fentanyl, we could discuss Chiavari chairs and macarons and dress shoes. Instead of bedsores and catheters, it’d be color schemes and updos and shrimp cocktail. Something to fight for, a celebration to look forward to.”

Michelle Zauner, Crying in H Mart (Page 129)

“This obsession with my mother’s caloric intake killed my own appetite. Since I’d been in Eugene, I’d lost ten pounds. The little flap of belly my mother always pinched at had disappeared and my hair began to fall out in large chunks in the shower from the stress. In a perverse way I was glad for it. My own weight loss made me feel tied to her. I wanted to embody a physical warning—that if she began to disappear, I would disappear, too.”

Michelle Zauner, Crying in H Mart (Page 100)