“Modern marketing culture is designed to amplify our desires. To turn faint wants into desperate needs. As a result, we’re intimately familiar with what we want. And we strive to get it. The problem with getting what you want is that now you have a hole, because you don’t want that thing anymore, you have it. We then are on a cycle, eager to find a new thing to want. Which means that the thing you used to want but now have fades in comparison. There’s a more resilient path: To commit to wanting what you have.”

Seth Godin

Discipline Is Destiny: The Power of Self-Control [Book]

![Discipline Is Destiny: The Power of Self-Control [Book] by Ryan Holiday Discipline Is Destiny: The Power of Self-Control [Book] by Ryan Holiday](https://movemequotes.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Discipline-is-Destiny-by-Ryan-Holiday.jpg)

Book Overview: To master anything, one must first master themselves–one’s emotions, one’s thoughts, one’s actions. Eisenhower famously said that freedom is really the opportunity to practice self-discipline. Cicero called the virtue of temperance the polish of life. Without boundaries and restraint, we risk not only failing to meet our full potential and jeopardizing what we have achieved, but we ensure misery and shame. In a world of temptation and excess, this ancient idea is more urgent than ever.

In Discipline is Destiny, Holiday draws on the stories of historical figures we can emulate as pillars of self-discipline, including Lou Gehrig, Queen Elizabeth II, boxer Floyd Patterson, Marcus Aurelius and writer Toni Morrison, as well as the cautionary tales of Napoleon, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Babe Ruth. Through these engaging examples, Holiday teaches readers the power of self-discipline and balance, and cautions against the perils of extravagance and hedonism.

At the heart of Stoicism are four simple virtues: courage, temperance, justice, and wisdom. Everything else, the Stoics believed, flows from them. Discipline is Destiny will guide readers down the path to self-mastery, upon which all the other virtues depend. Discipline is predictive. You cannot succeed without it. And if you lose it, you cannot help but bring yourself failure and unhappiness.

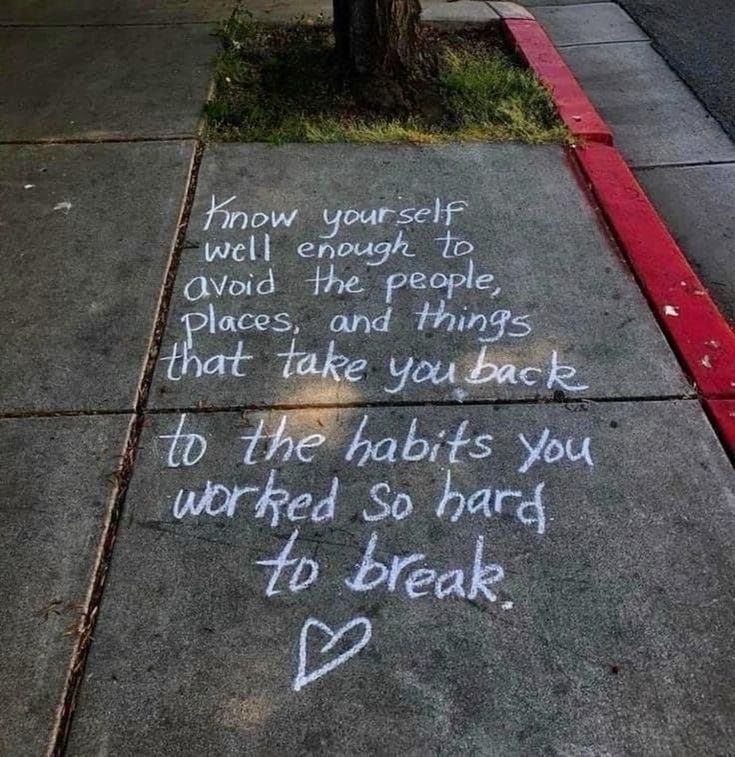

Don’t Let The Tame Ones Tell You How To Live [Poster]

Why We ♥ It: Some of the best advice I (Matt here) ever got was: don’t take life advice from people who aren’t living a life you want to live and don’t take criticism from people you wouldn’t go to for advice. I created this poster to act as a reminder to listen more closely to our role models and less closely to our critics, trolls, and tamed-comfort-zone-hugger acquaintances. It’s also a perfect gift for the outdoor adventurer, travel enthusiast, or solo explorer (or soon to be) who lives the anti-tame lifestyle and wants to beautifully illustrate it on the walls of their home (that they’ll rarely be there to see ;) Available in print or digital download.

9 Brian Tracy Quotes from No Excuses! and How To Lead A More Self-Disciplined Life

Excerpt: Living a self-disciplined life doesn’t have to be as hard as you think. Read these quotes from No Excuses! and learn how to make it easier…

Read More »9 Brian Tracy Quotes from No Excuses! and How To Lead A More Self-Disciplined Life

“A parent who acknowledges the fragility of life understands that every moment with their child is a gift not to be wasted. A wise parent looks at the world, harsh as it is, and says, ‘I see what you’re capable of, what you might do to my family tomorrow, but today, you’ve spared us. I will not take that for granted.’ That is how we must live—not just with our children, but with our wealth, our health, the peace in our country, the clear skies above.”

Ryan Holiday

“In an age where everyone appears to be producing constantly, it’s forgivable to assume you must be producing constantly too. If you are producing content, perhaps you should be. However, I don’t think you want to produce content. I think you want to make art. I think you need to make art. Art is a different animal entirely. It’s creation doesn’t abide by the same rules as content. Content is made for the masses and it is often soulless, plastic and easily replicable. Art, on the other hand, is self-expression. It’s soaked in your own blood. It’s as rich as figs drowning in a bowl of sugar and cream. It’s as unique as the Katana.”

Cole Schafer

“We all understand what optimism means; we all know what a relationship is. But the secret to finding contentment and fulfillment in your life is not understanding optimism, but living optimistically. It is not about intellectualizing the value of relationships, but diving in and allowing yourself to connect at an emotional level with someone else. Go ahead and care about your buddies at work or the barista who makes your coffee every day. These aren’t transactions—these are the jewels of life. Allow yourself to be vulnerable and take the risk of full engagement.”

Bert R. Mandelbaum, MD, via The Win Within (Page 144)

“When adversity or temptation arises, we are met with more than one path. Which path we take depends on our character. Just because one path appears to be paved with gold does not mean that it does not eventually turn to dirt. Those who choose the golden path cut corners and fail to adhere to values that are crucial to the character-building process. The glamour of instant gratification overshadows the reality of how it can affect our future. When it all falls apart, a lack of experience in dealing with adversity can leave us in a much worse situation than before. Nothing in life is free, and which every new path we must start from dirt and build our own golden road. The adversities we face along the way are all important building blocks to help us define the kind of person we want to become.”

Bert R. Mandelbaum, MD, via The Win Within (Page 140)

![Don’t Let The Tame Ones Tell You How To Live [Poster] Don’t Let The Tame Ones Tell You How To Live [Poster]](https://movemequotes.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Tame-Ones-Preview.jpg)